From Blank to Blank —

Emily Dickinson

A Threadless Way

I pushed Mechanic feet —

To stop — or perish — or advance —

Alike indifferent —

If end I gained

It ends beyond

Indefinite disclosed —

I shut my eyes — and groped as well

‘Twas lighter — to be Blind —

- In Chinese, ‘Blank’ is ‘Kongbai 空白’

Due to the state’s choice of censorship, independent publishing is substantially forbidden in China today, making it an underground activity. I only became aware of this reality recently when Xu Kuangzhi, founder as well as the only working staff of KONGBAI, was managing to publish and circulate my book on More’s Utopia with an ISBN acquired from Hong Kong. The book has been confidently polished to avoid sensitive words, phrases, rhetorics and controversial topics, protecting all in China involved (and will be involved) in producing and communicating this work.

In 2013, Xu, a sophmore at Central Acadmy of Fine Art in Beijing and has yet to physically travel to the West, personally initiated searching, collecting, translating, publishing, and circulating a vast bunch of Western art historical texts and critiques. In his words, he just loved to do it, even though he knew the number of readers would be very small. Gradually, many art history and literary scholars and professional translators, both inside China and studying abroad, volunteered to participate in Xu’s ambitious but quiet project by sharing original foreign texts and undertaking translation loads (mainly written and published in English, some in French and Japanese).

Unfortunately, Xu’s online platform, KONGBAI [Access to data 2015-21], with over 30,000 subscribers, was permanently suspended one day in October 2021 when he was translating Holland Cotter’s New York Times review of the Guggenheim Museum’s Art and China after 1989. The article was not so dangerous, and Xu wisely employed homophones and symbols to replace potentially sensitive words such as ’89’, ’64’, and ‘Ai Weiwei’. Xu had not published it in a digital form; he was revising it. Yet, all of a sudden, a short official notice shot him with a sense of threatening: ‘Someone had lodged a complaint against you’ (but in which no further detailed information was provided). It petrified Xu and all of us, unveiling the all-knowing digital Big Brother.

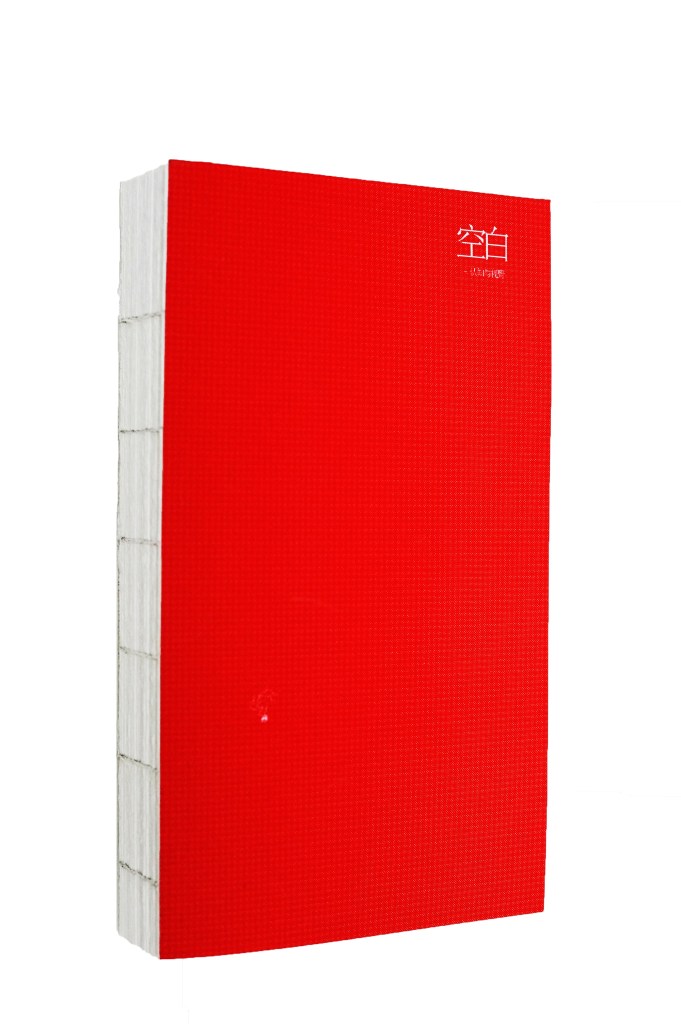

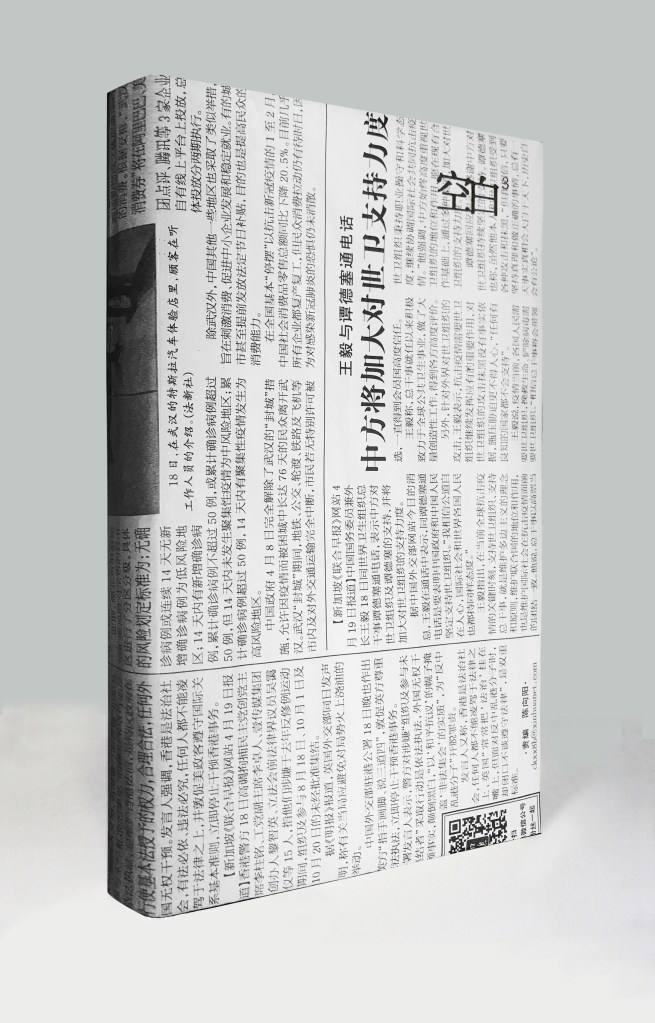

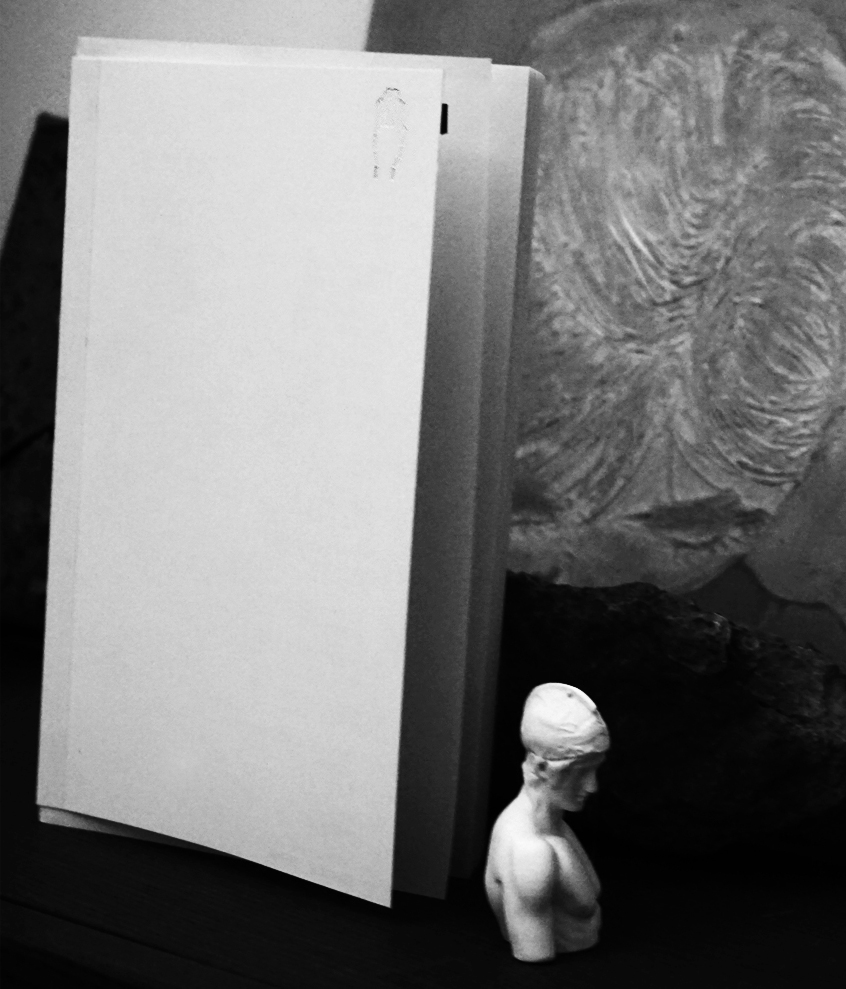

Many authors and online publishers in China, like Xu, have to prepare one or more alternative platforms to transfer their published but censored resources and redirect their readers to other virtual communities. There is an old Chinese idiom to describe them, ‘wily rabbits always have three burrows 狡兔三窟’. I prefer to call them ‘guerrilla authors’. Xu, an artist and book addict, also produces limited editions of paper books to display and reserve translations for inner-circle circulation. These exquisitely designed books could hardly be listed for sale as it is against the law to make money through any independent publication.

At the moment, the KONGBAI Series seems to be hardly used: neither in-class teaching nor seminar discussions. Xu once explained to me that the ‘core wisdom’ of the Chinese intelligentsia is to pick and make any foreign texts be used, not be read, generating pragmatic value that suits China’s situation to earn power. Once it is fully used (such as Marxism), it becomes propaganda.

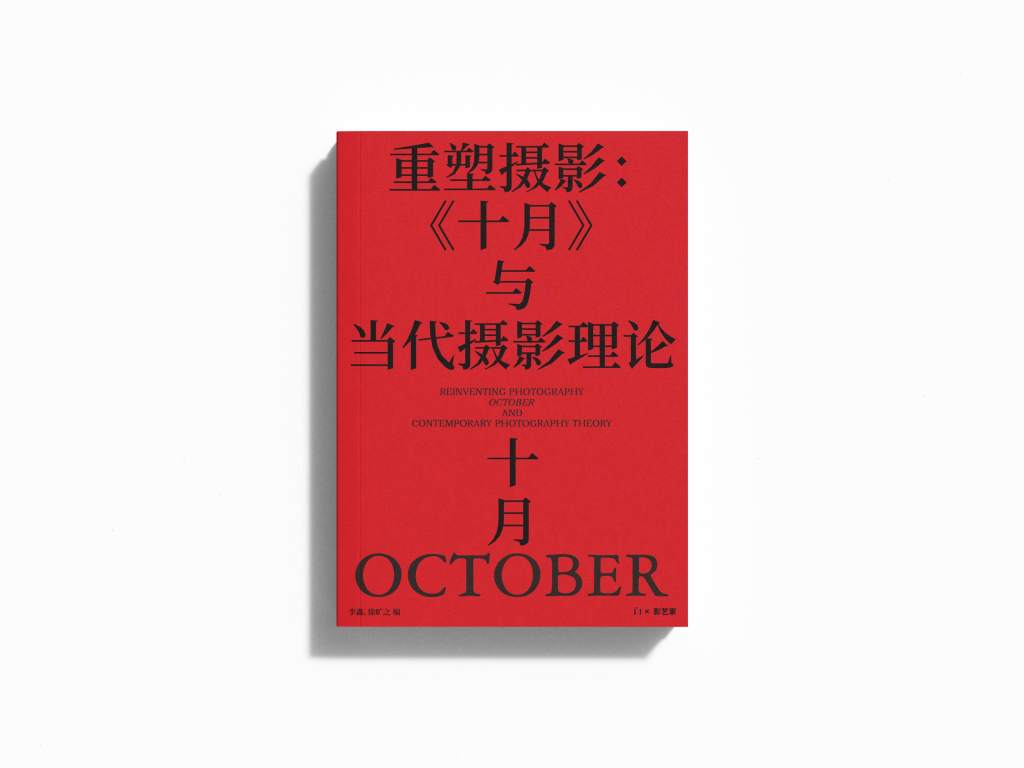

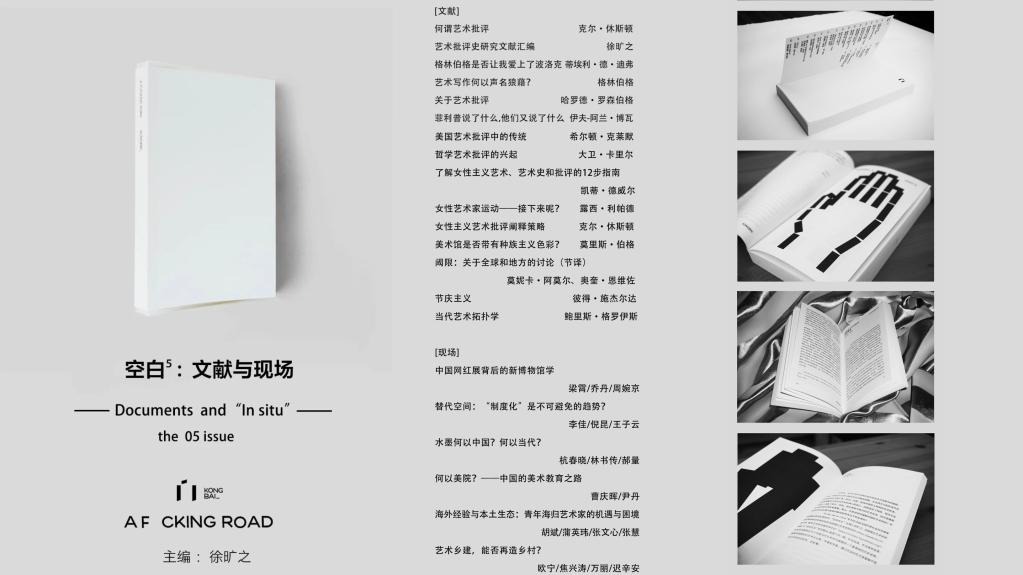

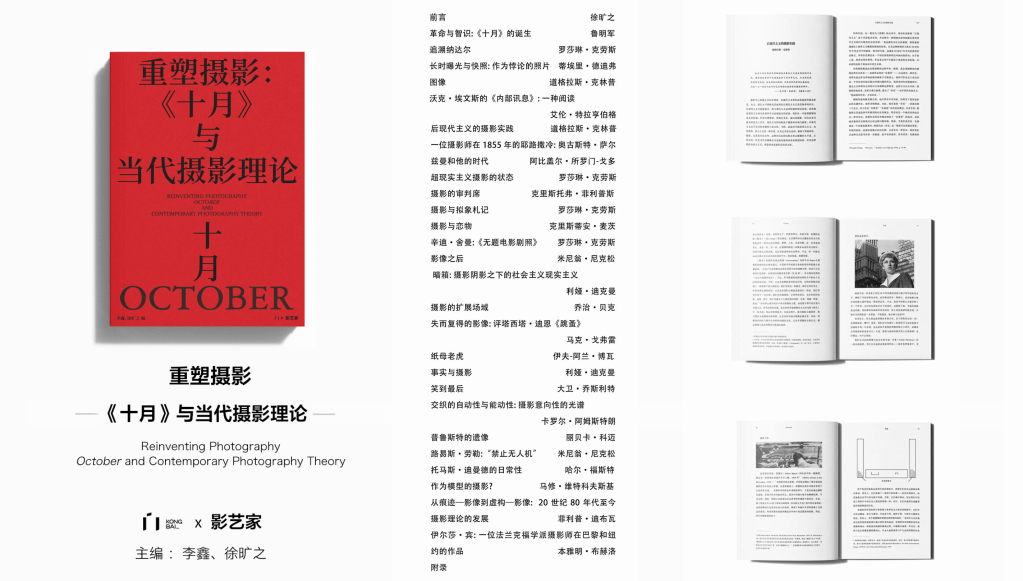

- KONGBAI [Blank 空白] Series 1-6.

- Image courtesy of Xu Kuangzhi [PhD in Art History and Theory]

Leave a comment